We worship a Mystery, a Being too vast to capture in words,

who reveals Godself to each of us in different ways.

While making room for different understandings,

let us affirm the faith that draws us together:

We believe in the God whose Word birthed the cosmos,

Who shaped human beings from the rich topsoil,

breathed Her own breath into us,

blessed both our earthy bodies and celestial spark,

and declared us Good, very Good!

When evil taught us shame

for those very bodies God had blessed,

God became a seamstress,

tenderly dressing Her children, Adam and Eve —

never dismissing our distress

but giving us what we need

to believe in our inherent dignity again.

This God reminds us at every opportunity

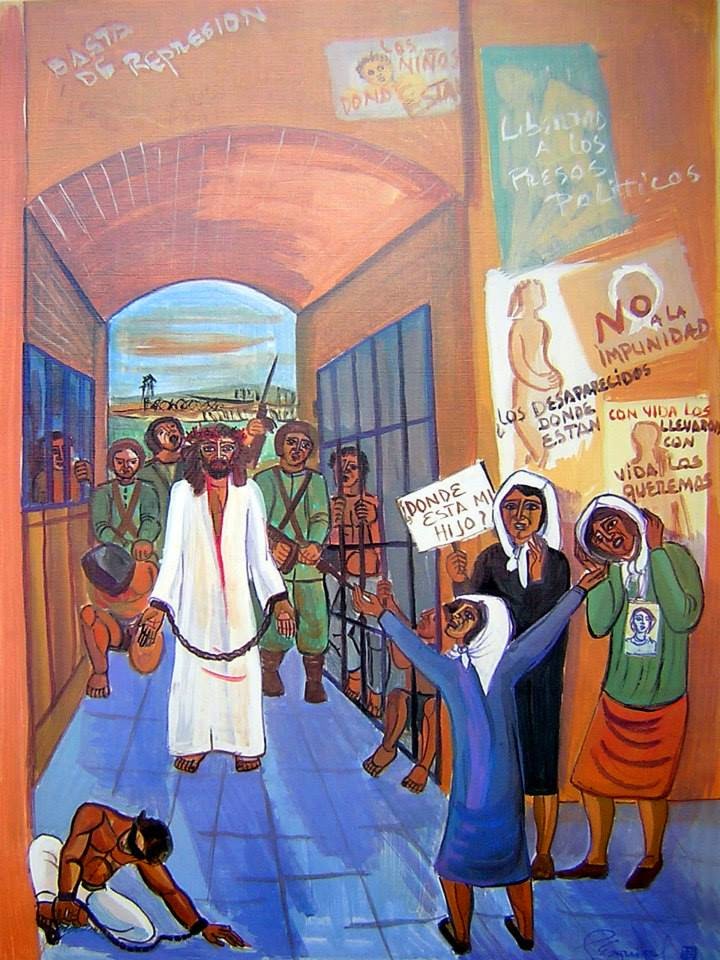

That we are destined for freedom:

God did what it took to liberate Her people

from enslavement in Egypt — and from countless future captors,

human powers who wield control through violence and fear.

The God who walked through Eden put on wheels —

the throne Ezekiel saw rolling through the heavens

to follow Their people into exile, and back again.

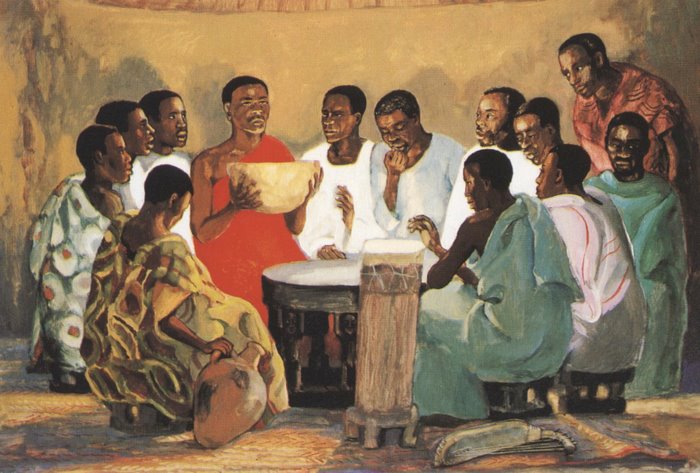

And then, this same God settled into flesh:

For God so loved the world They’d made

that They entered into it Themself,

weaving Godself a human form within a human womb.

From boundless power to an infant in the lap

of his teenage mother, God learned to crawl, to walk,

to speak with human tongue the news They’d been proclaiming

through pillars of flame and cloud,

through prophets’ cries and in the stillest silence.

In Jesus, God brought restoration to bodies and spirits aching

under the yoke of empire, the shackles of shame —

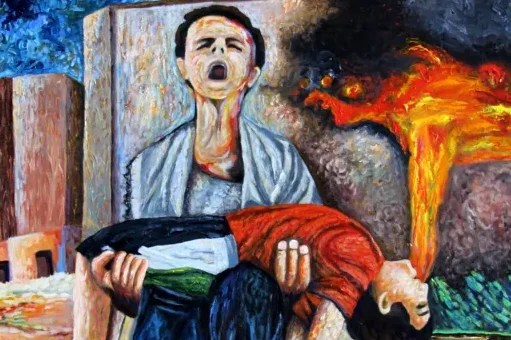

and then God died.

But no tomb can restrain Life itself for long:

Christ rose with wounds — reminders of what happens

when we allow violence and fear to reign unchallenged.

This wounded Christ ascended into heaven,

but his Spirit abides with us still —

stirring up our indifference, whispering hope into our despair,

and whisking us up into the hard but holy work

of unrolling a kin-dom accessible to all.

Amen.

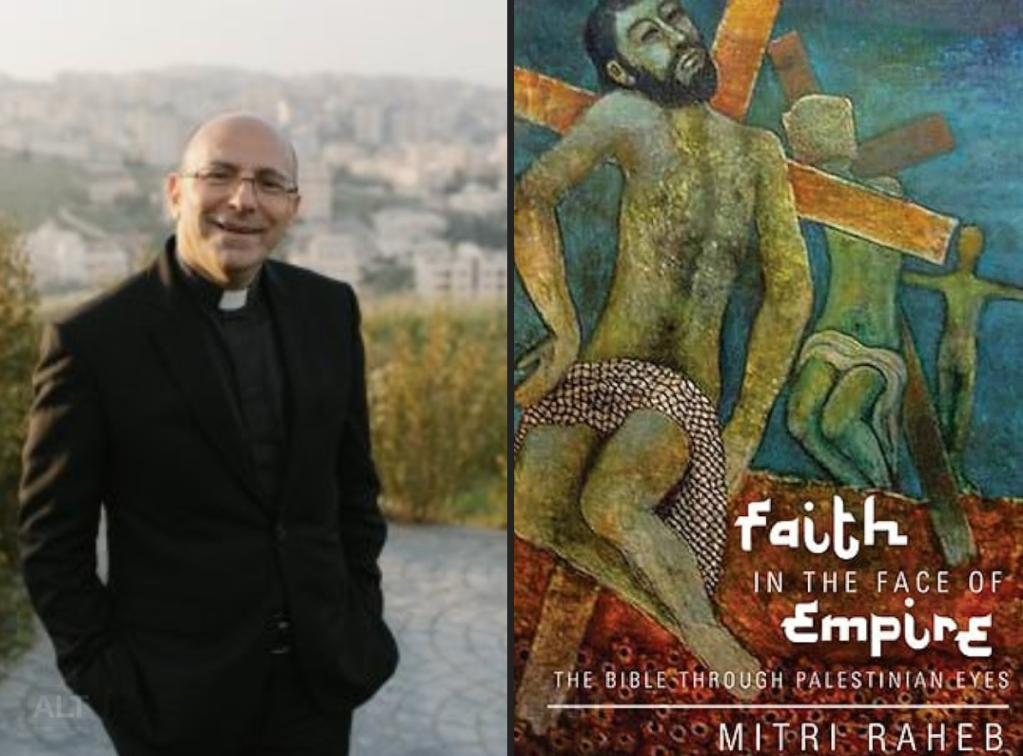

About this piece:

If you this piece it in your own service, please credit it to Avery Arden — and I invite you to email me at queerlychristian36@gmail.com to let me know you’re using it!

I wrote this affirmation for a worship service centered around John 20:19-30’s account of Jesus inviting Thomas to touch his wounds.

God created us to be inspirited bodies, embodied spirits — in Genesis 1, God calls not just our spirits but our bodies good — and not just some bodies, but all bodies, disabled bodies included.

Disability theologians have long been inspired by the idea that Jesus’s resurrected body keeps its wounds — wounds that would impair mobility and fine motor skills, that would cause chronic pain.

In rising with a disabled body, Jesus “redeems” disability: he evinces that disability is not brokenness, is not shameful or the result of sin; and he evinces that disability can exist separate from suffering — that suffering is not intrinsic to disability.

The idea of a wounded Christ also connects to Henri Nouwen’s concept of the “wounded healer,” which I recommend looking into if that phrase resonates with you.

The description of God as seamstress restoring a sense of dignity to Adam and Eve is inspired by Cole Arthur Riley’s book This Here Flesh, where she writes:

“On the day the world began to die, God became a seamstress. This is the moment in the Bible that I wish we talked about more often.

When Eve and Adam eat from the tree, and decay and despair begin to creep in, when they learn to hide from their own bodies, when they learn to hide from each other—no one ever told me the story of a God who kneels and makes clothes out of animal skin for them.

I remember many conversations about the doom and consequence imparted by God after humans ate from that tree. I learned of the curses, too, and could maybe even recite them. But no one ever told me of the tenderness of this moment. It makes me question the tone of everything that surrounds it.

In the garden, when shame had replaced Eve’s and Adam’s dignity, God became a seamstress. He took the skin off of his creation to make something that would allow humans to stand in the presence of their maker and one another again.

Isn’t it strange that God didn’t just tell Adam and Eve to come out of hiding and stop being silly, because he’s the one who made them and has seen every part of them? He doesn’t say that in the story, or at least we do not know if he did. But we do know that God went to great lengths to help them stand unashamed. Sometimes you can’t talk someone into believing their dignity. You do what you can to make a person feel unashamed of themselves, and you hope in time they’ll believe in their beauty all on their own.

…

People say we are unworthy of salvation. I disagree. Perhaps we are very much worth saving. It seems to me that God is making miracles to free us from the shame that haunts us. Maybe the same hand that made garments for a trembling Adam and Eve is doing everything he can that we might come a little closer. I pray his stitches hold. Our liberation begins with the irrevocable belief that we are worthy to be liberated, that we are worthy of a life that does not degrade us but honors our whole selves. When you believe in your dignity, or at least someone else does, it becomes more difficult to remain content with the bondage with which you have become so acquainted. You begin to wonder what you were meant for.

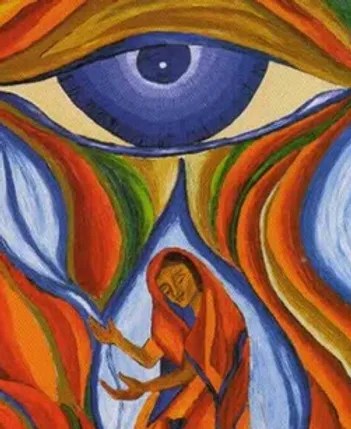

The idea of God on wheels comes primarily from Julia Watts Belser’s article “God on Wheels: Disability and Jewish Feminist Theology.” I highly recommend the whole article (check out the gorgeous art piece that accompanies it, if nothing else), but here’s one excerpt:

“…On the morning of the holiday of Shavuot, Jewish communities around the world chant from the book of Ezekiel, reciting the Israelite prophet’s striking image of God. The prophet speaks of a radiant fire borne on a vast chariot, lifted up by four angelic creatures with fused legs, lustrous wings, and great wheels. …One recent Shavuot, Ezekiel’s vision split open my own imagination. Hearing those words chanted, I felt a jolt of recognition, an intimate familiarity. I thought: God has wheels!

When I think of God on wheels, I think of the delight I take in my own chair. I sense the holy possibility that my own body knows, the way wheels set me free and open up my spirit. I like to think that God inhabits the particular fusions that mark a body in wheels: the way flesh flows into frame, into tire, into air. This is how the Holy moves through me, in the intricate interplay of muscle and spin, the exhilarating physicality of body and wheel, the rare promise of a wide-open space, the unabashed exhilaration of a dance floor, where wing can finally unfurl.

On wheels, I feel the tenor of the path deep in my sinews and sit bones. I come to know the intimate geography of a place: not just broad brushstrokes of terrain, but the minute fluctuations of topography, the way the wheel flows. When I roll, I pay particular attention to the interstices and intersections: the place where concrete seams together uneasily, the buckle of tree roots pushing up against asphalt, the bristle of crumbling brick.

I have come to believe this awareness reflects a quality of divine attention. Perhaps the divine presence moves through this world with a bone-deep knowledge of every crack and fissure. Perhaps God is particularly present at junctions and unexpected meetings, alert to points of encounter where two things come together…”

A similar theology around God on wheels can be found in the perspective of a Christian teen named Becky Tyler, found here. Becky says:

“When I was about 12 years old, I felt God didn’t love me as much as other people because I am in a wheelchair and because I can’t do lots of the things that other people can do. I felt this way because I did not see anyone with a wheelchair in the Bible, and nearly all the disabled people in the Bible get healed by Jesus – so they are not like me.”

She felt alienated by much of what she read in the Bible – until she was given new food for thought.

“My mum showed me a verse from the Book of Daniel (Chapter 7, Verse 9), which basically says God’s throne has wheels, so God has a wheelchair.

“In fact it’s not just any old chair, it’s the best chair in the Bible. It’s God’s throne, and it’s a wheelchair. This made me feel like God understands what it’s like to have a wheelchair and that having a wheelchair is actually very cool, because God has one.”