This year the lectionary gives us Mark’s account of the Resurrection, with its fearful cliffhanger ending — an empty tomb, but Jesus’s body missing. And isn’t that unresolved note fitting?

In the face of so much suffering across the world, it feels right to be compelled to sit — even on this most jubilant of days — with the poor and disenfranchised in their continued suffering.

Mark’s account:

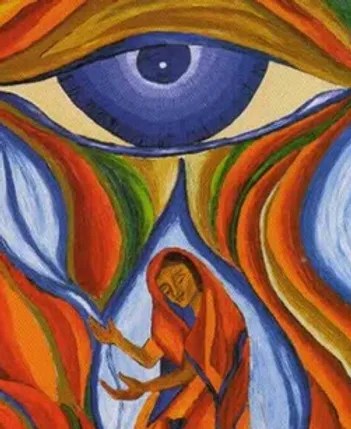

Just days before, the women closest to Jesus witnessed him slowly suffocate to death on a Roman cross. Now, now trudge to his tomb to anoint his corpse — and find the stone rolled away, his body gone. A strange figure inside tells them that Jesus is has risen, and will reunite with them in Galilee.

They respond not with joy, but trembling ekstasis — a sense of being beside yourself, taken out of your own mind with shock. They flee.

The women keep what they’ve seen and heard to themselves — because their beloved friend outliving execution is just too good to be true. When does fortune ever favor those who languish under Empire’s shadow?

Love wins, yet hate still holds us captive.

I’m grateful that Mark’s resurrection story is the one many of us are hearing in church this year. His version emphasizes the “already but not yet” experience of God’s liberation of which theologians write: Christians believe that in Christ’s incarnation — his life, death, and resurrection — all of humanity, all of Creation is already redeemed… and yet, we still experience suffering. The Kin(g)dom is already incoming, but not yet fully manifested.

Like Mark’s Gospel with its Easter joy overshadowed by ongoing fear, Trans Day of Visibility is fraught with the tension of, on the one hand, needing to be seen, to be known, to move society from awareness into acceptance into celebration; and, on the other hand, grappling with the increased violence and bigotry that a larger spotlight brings.

The trans community intimately understands the intermingling of life and death, joy and pain.

When we manage to roll back the stones on our tombs of silence and shame, self-loathing and social death, and stride boldly into new, transforming and transformative life — into trans joy! — death still stalks us.

We are blessedly, audaciously free — and we are in constant danger. There are many who would shove us back into our tombs.

And of course, the trans community is by no means alone in experiencing the not-yet-ness of God’s Kin(g)dom.

Empire’s violence continues to overshadow God’s liberation.

The women who came to tend to their beloved dead initially experienced the loss of his body as one more indignity heaped upon them by Empire. Was his torture, their terror, not enough, that even their grief must be trampled upon, his corpse stolen away from them?

The people of Gaza are undergoing such horrors now. Indignity is heaped on indignity as they are bombed, assaulted, terrorized, starved, mocked. They are not given a moment’s rest to tend to their dead. They are not permitted to celebrate Easter’s joy as they deserve. They are forced to break their Ramadan fasts with little more than grass.

Those of us who reside in the imperial core — as I do as a white Christian in the United States — must not look away from the violence our leaders are funding, enabling, justifying.

We must not celebrate God’s all-encompassing redemption without also bearing witness to the ways that liberation is not yet experienced by so many across the world.

This Easter, I pray for a free Palestine. I pray for an end to Western Empire, the severing of all its toxic tendrils holding the whole earth in a death grip.

I pray that faith communities will commit and recommit themselves to helping roll the stones of hate and fear away — and to eroding those stones into nothing, so they cannot be used to crush us once we’ve stepped into new life.

I pray for joy so vibrant it washes fear away, disintegrates all hatred into awe.

In the meantime, I pray for the energy and courage to bear witness to suffering; for the wisdom for each of us to discern our part in easing pain; for God’s Spirit to reveal Xirself to and among the world’s despised, over and over — till God’s Kin(g)dom comes in full at last.