During the season of Advent, Christians traditionally read Luke’s and Matthew’s Nativity stories alongside the book of Isaiah. It makes sense to do so, as Matthew himself makes the connection:

22 Now all of this took place so that what the Lord had spoken through the prophet would be fulfilled:

23 Look! A virgin will become pregnant and give birth to a son,

And they will call him, Emmanuel. (Matthew 1:22-23)

– Matt 1:22-23, referencing Isaiah 7:14

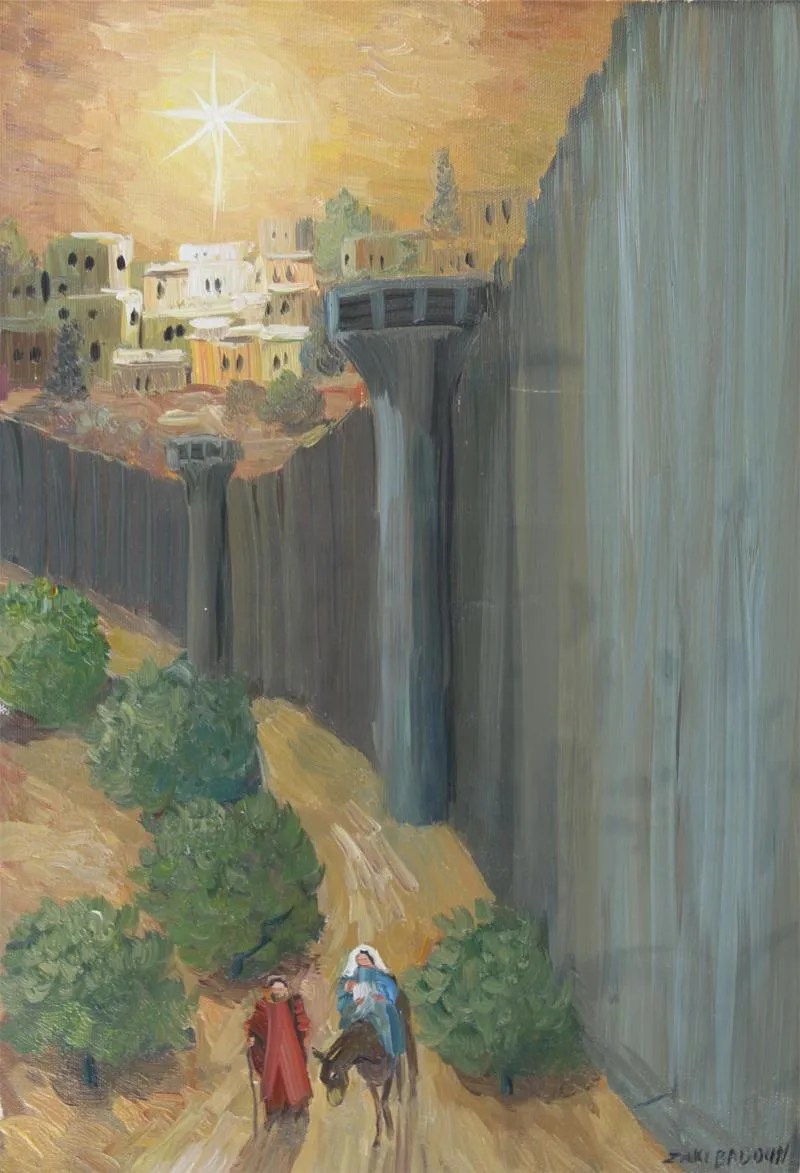

But when we read Isaiah only in service to our Christian story, we do harm to our Jewish neighbors with whom we share these scriptures. To utilize the Hebrew Bible (= “Old Testament,” the Jewish Bible) solely as a promise fulfilled through Christ is to suggest that these scriptures are incomplete without and dependent upon Jesus — and therefore that Jews’ interpretation of their own Bible is incorrect and irrelevant.

So how do we simultaneously honor our Advent traditions, draw from Isaiah’s wisdom, and respect the vibrant, living faith of our Jewish neighbors?

Dr. Tyler Mayfield provides some excellent options in his 2020 book Unto Us a Son Is Born: Isaiah, Advent, and Our Jewish Neighbors.

The purpose of this post is to share some of the wisdom from Mayfield’s work, and to urge pastors, teachers, and others who help shape the Advent experience for their communities to check out the entire text for even more invaluable commentary.

Contents of Unto Us a Child Is Born:

- An introduction that, well, introduces the issues with current Christian uses of Isaiah and suggests a bifocal framework as remedy

- Chapter 1: Using Our Near Vision During Advent

- Chapter 2: Using Our Far Vision to Love Our Jewish Neighbors

- The remainder of the chapters delve into each of the Isaiah passages offered by the Revised Common Lectionary for the Advent season.

This post will survey key points from the intro and first two chapters, and close with actionable ways to incorporate Mayfield’s message into Sunday worship and classes. Preachers and teachers will find it immensely helpful to read the rest of the book’s chapters as lesson/sermon preparation for each week of Advent.

The Bifocal Lens

In order to maintain our Christian traditions without monopolizing the Hebrew Bible, Mayfield recommends a bifocal view:

- Our near vision focuses on our worship practices and liturgical celebrations, grounding us in our living religious tradition;

- Our far view pays attention to the ways those practices affect those not in our communities and “compels us to critique and reject some aspects of this tradition, those that are hurtful, inaccurate, and derogatory toward our religious neighbors” (intro).

Using Isaiah and other Jewish scriptures responsibly during worship is not merely a scholarly endeavor; as Mayfield reminds us, reading and interpreting the Bible is a matter of ethics:

[…L]iturgy and ethics are not easily separated. In her excellent and provocative book on racism and sexism in Christian ethics, Traci West notes, “The rituals of Sunday worship enable Christians to publicly rehearse what it means to uphold the moral values they are supposed to bring to every aspect of their lives, from their attitudes about public policy to their intimate relations.” …We want our worship to spur us to live out our ethical claims. (Introduction)

Using Mayfield’s bifocal lens, we can ethically navigate “the tension between identity within a particular faith tradition and openness to the faith traditions of others.”

So what are some of the ways that traditional Advent worship can lead us to do harm to our Jewish neighbors?

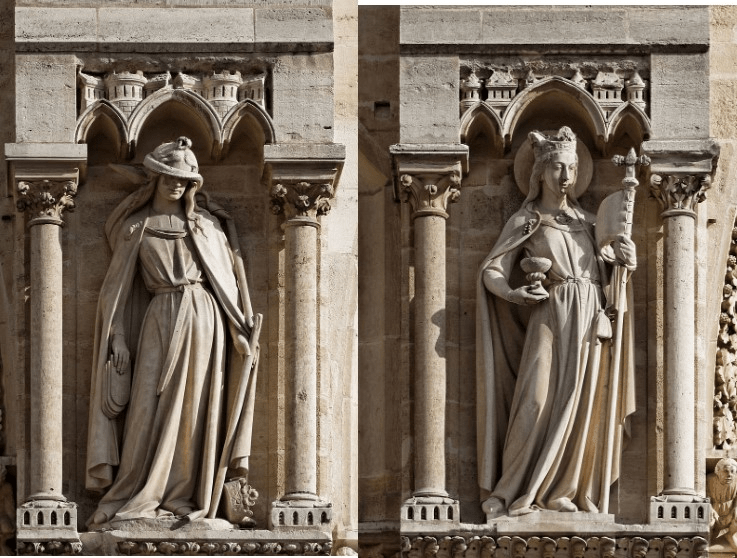

Supersessionism

Supersessionism, also called replacement theology, claims that Christianity has replaced or supplanted Judaism; that our covenant through Christ cancels out Jews’ covenant through Abraham and Moses (hence the labeling of the two parts of the Christian Bible as the Old and New Testaments, from the Latin word for covenant).

Mayfield brings in Susannah Heschel’s description of supersessionism as a “theological colonization of Judaism“; she defines it as:

“The appropriation by the New Testament and the early church of Judaism’s central theological teachings, including messiah, eschatology, apocalypticism, election, and Israel, as well as its scriptures, its prophets, and even its God, while denying the continued validity of those teachings and texts within Judaism as an independent path to salvation.” (Heschel, The Aryan Jesus, 2008)

The seeds that the early church planted have born violent fruit across the centuries. This attitude of judgment and/or pity has led both to ideological violence — “render[ing] Jews invisible or irrelevant or as incomplete Christians” (intro) — and immense physical violence through to the segregation, scapegoating, forced conversions, expelling, and flat-out murder of the Jewish people across multiple continents.1

There are multiple instances of the Talmud — the central text of rabbinical Judaism alongside the Jewish Bible — being likewise gathered and burned across Medieval Europe due to the anti-Jewish belief that the Talmud was the primary obstacle keeping Jews from converting to Christianity. In 1242, for instance, King Louis IX of France ordered the burning of “24 cartloads” — something like 12,000 volumes — of priceless, scribe-written copies of the Talmud. This event devastated France’s Jewish community, which had been one of the seats of Jewish scholarship. Louis also followed up the book burning with a decree to expel all Jews from France: violence against Jewish scripture goes hand-in-hand with violence against Jewish bodies.

All this to say, the views we shape through worship and elsewhere truly do have real-world implications.

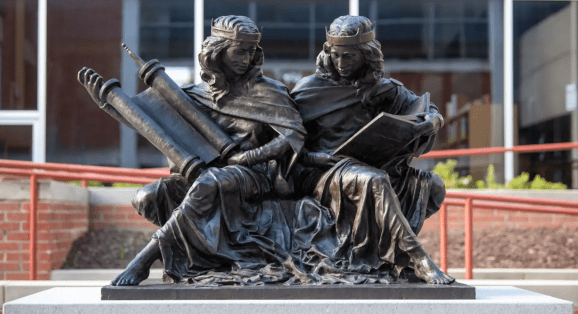

Mayfield argues that it is possible — indeed, necessary — to share scriptures respectfully. After all, he says, Judaism and Christianity are siblings.

While Christianity is often envisioned as the “shoot” growing from the dead stump of Jesse in Isaiah 11:1, a child who has improved upon the parent, in reality Judaism and Christianity are more like two branches extending from the same tree. They “grew out of the same milieu,” developing from the religion depicted in the Hebrew Bible during the chaotic era of that first century CE:

While early Jesus followers were formulating an identity distinct from Christ’s Jewish origins, Rome’s 70 CE destruction of the Second Temple spurred on new iterations of Jews’ own religion; following the Pharisees,2 they recentered faith around local life rather than the temple. In this way, the two religions are around the same age, growing from the same foundations! We are sibling religions; and we are neighbors. The problem is that we Christians have frequently behaved as very poor neighbors indeed.

Why Jewish “Neighbors”?

In Isaiah, Advent, and Our Christian Neighbors, Mayfield has opted for the term neighbor to describe the Christian relationship to Jews in the present day. Why? For one thing, love of neighbor is a central tenet of both Jewish and Christian tradition, originating in Leviticus 19:18 and emphasized by Jesus in Mark 12:31 and Matthew 22:39. Reading scripture through the ethic of love thy neighbor, we must ask, “If a particular reading of Scripture leads us to think badly of Jews, then is this reading Christian?” (chapter 2).

Furthermore, Mayfield continues,

I also use the concept of neighbor because neighbors do not always agree. In fact, they sometimes disagree and have to take seriously one another’s perceptions, feelings, and opinions. Being neighborly is being attentive and listening well to the concerns of others. It is realizing that your actions affect those around you. Christians act neighborly when they take seriously Jewish critiques of Christianity and Christian teachings, just as Jews act neighborly when they offer these critiques. (Chapter 2)

In reconsidering how we read and teach scripture, we can imagine that scripture is the fence we share with our Jewish neighbors, even while we dwell in different “geographies.” But when we accept supersessionist theology, we deny Jews their side of the fence; we colonize it.

Let’s look at how supersessionism manifests specifically in the ways we use Isaiah during Advent.

Resisting a Christian Isaiah

Mayfield describes how, over the past two millennia, Christians have disconnected Isaiah from his ancient Jewish context and Christianized him, even going so far as to call this eighth-century BCE prophet’s book the “fifth Gospel” alongside Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John (intro).

In lifting Isaiah from his seat among Jeremiah, Amos, and all the Hebrew Bible’s prophets, we sever him from his original ancient Jewish audience and deny his relevance to our Jewish neighbors today.

We hear Isaiah (and Handel in his Messiah) proclaim: “For unto us a child is born; unto us a son is given” (Isaiah 9:6) and everything in our tradition preps us to assume that the “us” in question is us Christians; that this child must be Jesus!

In our presumption that Isaiah’s prophecies are all about Jesus, we render this prophet irrelevant to our Jewish neighbors, denying the validity of their interpretations of this biblical book. But if we dig into the historical context, we can broaden our ways of understanding these texts and thus learn how to better share these scriptures.

A Christ-exclusive interpretation of Isaiah misunderstands what biblical prophets did.

We hear the word “prophecy” and think of foreseeing the future, often the distant future. But the prophets of the Bible, from Joel to John the Baptist, were largely focused on their own here-and-now:

The prophets of ancient Israel (and ancient Mesopotamia) did not see their sole activity as foretelling. They were also “forthtellers,” speaking to the religious and political issues of their day with courage and strength. As mediators between God and the people, prophets delivered messages, oracles, and visions to audiences that included kings and commoners. They interpreted the past, analyzed the present, and spoke of the future but were undoubtedly more concerned with events of the present than events several hundred years in the making. …

[T]he notion of prophecy as foretelling renders the prophet’s words irrelevant to, and uninspired for, the first hearers and readers of these messages. (Chapter 1)

There’s another historical issue with reading Isaiah’s prophecies as exclusively about Jesus as his people’s anticipated Messiah:

At the time of Isaiah in the 700s BCE, the concept of the eschatological Messiah had not yet been developed!

While the Hebrew Bible does describe figures like David and Cyrus as anointed ones (which is what the Hebrew word mashiach, “messiah,” means), the concept of The Messiah who would usher in an age of justice and peace was most likely a later development of Second Temple Judaism (516 BCE – 70 CE).

We only see The Messiah in Isaiah’s descriptions of a “Wonderful Counselor…Prince of Peace” (Isaiah 9:6b) and a just judge on whom God’s spirit rests (Isaiah 11:1-10) because of our own bias: “We think we know what we will find before we look” (chapter 1).

Learning about a passage’s original context helps us interpret the text more faithfully as we seek its relevance today. What is more, we can and should consider its multiple historical contexts, the whole breadth of what it has meant for different groups in different eras:

Texts in Isaiah have an entire history of interpretation, which includes the “originating” context in ancient Israel, their reuse and interpretation in Second Temple Judaism perhaps, their Christian context in which some Isaiah texts became christological, the Jewish context in which some texts became messianic, and then later Christian context, that is, when these texts were attached to Advent.

The book of Isaiah was composed by ancient Israelites over several centuries, from the eighth to the fifth centuries BCE. These authors wrote for their ancient Israelite audiences with no comprehension of later events such as the life of Jesus and the growth of Christianity. Thus, the book of Isaiah does not predict the birth of Jesus. (Chapter 1)

Recognizing the long history of a piece of scripture helps reduce our sense of ownership over the text; we realize that its messages are not for Christians alone, but for faithful Jews and Christians (and Muslims, to an extent) across the millennia and today. This recognition is vital for unpacking biases and beliefs we often don’t even realize we carry deep in our psyches — and that some of the tools we use reinforce.

A Complicit Lectionary?

A key concern Mayfield explores throughout Unto Us a Child Is Born is how the lectionaries we use can guide us towards supersessionist readings during Advent. He focuses on the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL) because of its popularity: Denominations ranging from the UCC to the Roman Catholic Church make use of it; overall, a huge portion of all sorts of Christians (largely in Canada and the USA) use it.

Mayfield explains that for each Sunday, the ecumenical team that created the RCL selected the Gospel reading first, and then selected an “Old Testament” text (plus a psalm & Acts/epistles/Revelation passage) to complement that Gospel reading.

The theological ramifications of always prioritizing the Gospel in this way include an unbalanced dialogue: If we imagine the readings in conversation with each other, the Gospel always gets to choose the topic; the “Old Testament” only ever gets to respond.

Actionable Ways to Be Good Neighbors

After learning about Advent’s supersessionist pitfalls, you might be tempted simply to drop Isaiah in an effort to avoid the issue entirely. But Mayfield argues that that is a mistake:

We need Isaiah to celebrate Advent. The book’s treasures are too marvelous to set aside as ancient history or consign to another liturgical season. As we begin the liturgical year, we need to hear of swords beaten into plowshares and of barren lands blooming. …To use only the Gospel readings during Advent limits our theological reflections while also insinuating that only those four biblical books are worthy of public reading and proclamation. (Chapter 1)

Instead of ditching Isaiah, Mayfield offers practical suggestions for using the prophet responsibly:

First, we can open readings of Isaiah in church with an explicit statement: “Today we hear words from a book held sacred by both Jews and Christians.” As Mayfield explains, “This simple and accurate statement…compels us to recognize our religious neighbors even as we worship” (chapter 2).

Going further, a preacher can remind congregants that “As Christians, we understand Isaiah through our histories and theologies, but Jews do not read Isaiah this way.”

(My own thought: A pastor can even take time in an Advent sermon to acknowledge some of the history of misusing Jewish scriptures / debunking common presumptions about Isaiah’s role in the Nativity story. A Sunday School teacher has even more space to explore that history and context, and to invite attendees to imagine how Isaiah speaks to us today.)

Beyond simple statements and one-time mentions, Mayfield urges us to commit to always interpreting scriptures through a paradigm of “do no harm” — to “share as good neighbors.”

A key part of this paradigm is an intentional shift from “a more linear approach to the narrative of Scripture (in which we read the biblical books as a progression both in time and in theological depth) to a more back-and-forth conversational approach (in which we allow various texts to speak to one another).” This conversational framework creates space for the Bible’s many voices and refuses to let “New Testament” voices dominate.

Here’s a longer excerpt from Mayfield describing how to put this paradigm into practice while remaining true to ourselves:

So, how do we, as Christians, continue to affirm one of our central claims of Jesus as the Messiah while also allowing space for the dismissal of that claim? Perhaps we are helped by returning to the tension between identity and openness.

Christians maintain strong identities in the claim of Jesus as the Christ while also remaining open to other visions of the messianic kingdom, thus realizing that the full realm of God has not come. It is vital to our identity to claim Jesus as the Messiah, and we are also open to other formulations of messiah.One meaningful way forward along this challenging path is not to claim too much: to be careful, considerate, and humble with our messianic notions. For example, instead of holding to a messianic or christological reading of Isaiah as the only valid notion, Christians could admit openly and explicitly that these texts provide some of the necessary elements that will constitute notions of messiahship in first-century Judaism, notions Jesus and his biographers took up and used. However, these texts do not point immediately to Jesus; there is just not a straight line — historically or theologically — between Point A, Isaiah, and Point B, Jesus.

This sort of admission presents real possibilities for neighborly engagement since it ties the Christian claim about Jesus more closely to sacred texts that are used only by Christians. It does not predetermine the meaning of Isaiah for all traditions, but it allows Jews and Christians to interpret Isaiah’s prophecies based on their respective traditions, with neither tradition holding ultimate authority over the biblical text. …We could go even further to say that the Jewish reading is an important and necessary one from which Christians could learn. (Chapter 2)

More Benefits of Interpreting Responsibly!

Ultimately, a paradigm of respect and mutual conversation bears rich fruit not only in our relationship to our Jewish neighbors, but to our own faith. Letting Hebrew Bible texts stand on their own merit opens us to how a given passage speaks to us here and now, rather than limiting its prophecies to a closed loop of prophecy-fulfilled-in-Christ. Mayfield quotes Ellen Davis’ comment that

“We like to keep the frame of reference for prophecy within the ‘safe’ confines of the Bible, by reading prophecy solely as illuminating what has already happened—the birth, life, and death of Jesus Christ—and not allowing it to meddle much in the current lives of Christians” [and Jews!]. (Chapter 1)

We are not called to play it safe; we are called to let scripture breathe, and to welcome in God’s mischievous spirit! Making room for many interpretations, for multiple messages from Isaiah for different times and contexts, liberates scripture to speak to us in new, challenging, relevant ways today.

Doing so also helps us live into the tension of Advent’s dual theological themes: Incarnation and eschatology. As Mayfield notes,

These two foci do not naturally cohere. The emotions invoked by Advent call us to “prepare joyfully for the first coming of the incarnate Lord and to prepare penitently for the second coming and God’s impending judgment.”3 Joy and penitence. …We are pulled in different emotional directions. (Chapter 1)

Churches tend to lean towards the joy — but we can’t ditch the solemnity, can’t “alleviate the tension,” without robbing ourselves of “the incredible richness and grace that result from the annual eschatological collision in the weeks before Christmas.”4

As someone who centers my ministry around breaking binaries, reveling in the in-betweens where God does Their best work, I appreciate this insistence on the “both/and” of penitence and joy — as well as of Isaiah and Matthew/Mark, and of a prophetic message for Isaiah’s time, and Jesus’s time, and for us and our Jewish neighbors today.

Closing

In Advent, past, present, and future queerly coalesce:

“We have hope in what the incarnation brings to our world each day, even as we hope for the setting right of things with the culmination of history.” (Chapter 1)

Though the details certainly differ, we can thus proclaim that “even though the Messiah has come, we wait with Jews for the ‘complete realization of the messianic age'” and that in this interim time, “it is the mission of the Church, as also that of the Jewish people, to proclaim and to work to prepare the world for the full flowering of God’s Reign, which is, but is ‘not yet’”5 (chapter 2).

This Advent claim “takes the unique identity of Christians seriously as ones who have seen in Jesus our Messiah yet remain open to the fullness of that claim in the future” (chapter 2).

It is possible to shape Advent into a season wherein we don’t perpetuate harm against our Jewish neighbors, but rather grow in our respect for and mutual relationship with them. The remainder of Unto Us a Child Is Born: Isaiah, Advent, and Our Christian Neighbors is overflowing with more knowledge and advice that further enables this aim. I highly recommend checking it out. If you need help obtaining a copy, hit me up.

Have a blessed, pensive, and joyful Advent.

- For a thorough history of antisemitism, and how to be in solidarity both with Jews and Palestinians, I highly recommend Safety through Solidarity: A Radical Guide to Fighting Antisemitism. ↩︎

- Pharisees were cool, y’all; go learn from the fabulous Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg about what Pharisees believed, how Jesus may have been a Pharisee himself, and the context around the Gospel writers’ negative depictions of them ↩︎

- Mayfield’s quoting Gail R. O’Day, “Back to the Future: The Eschatological Vision of Advent” (2008) ↩︎

- Mayfield’s quoting J. Neil Alexander, Waiting for the Coming (1993) ↩︎

- Mayfield is quoting Mary Boys, Has God Only One Blessing? (2000) ↩︎

![a detail from a painting, showing a flipped tables and a mess of coins and sheep and doves. There’s another quote from Levine reading, “Pilgrims…would not bring [sacrificial] animals with them from Galilee or Egypt or Damascus. They would not risk the animal becoming injured and so unfit for sacrifice. The animal might fly or wander away, be stolen, or die. …One bought one’s offering from the vendors. And…there is no indication that the vendors were overcharging or exploiting the population. The people would not have allowed that to happen. Thus, Jesus is not engaging in protest of cheating the poor.”](https://binarybreakingworship.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/tumblr_9695db8e3beb683c8e70b44fb07cc4a8_2af7c102_1280-2.png?w=960)

![a detail of an illustration of a courtyard in the Temple with large pillars and crowds of people, with a quote from Levine’s chapter reading, “…The Temple has an outer court, where Gentiles are welcome to worship. They were similarly welcome in the synagogues of antiquity, and today. They do not have the same rights and responsibilities as do Jews, and that makes sense as well. When I [a Jewish woman] visit a church, there are certain things I may not do. …”](https://binarybreakingworship.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/tumblr_9234a5643ec77b949fe4006a947cb6d7_6948717c_1280-1.png?w=960)