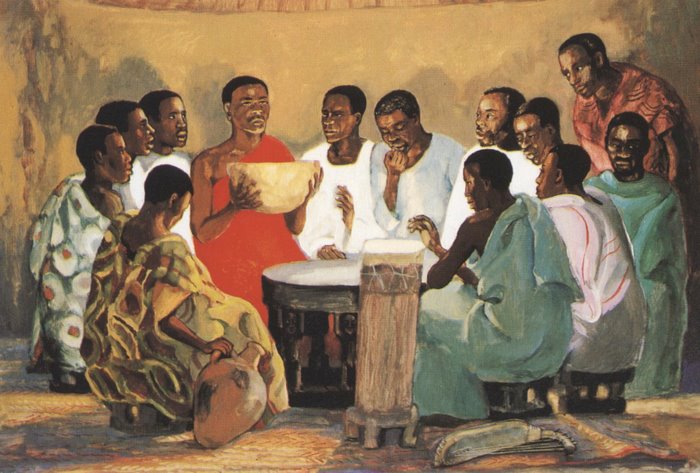

Today is Maundy Thursday, when Christians remember Jesus’s Last Supper, his final meal with his closest friends before his arrest and execution by the Roman Empire.

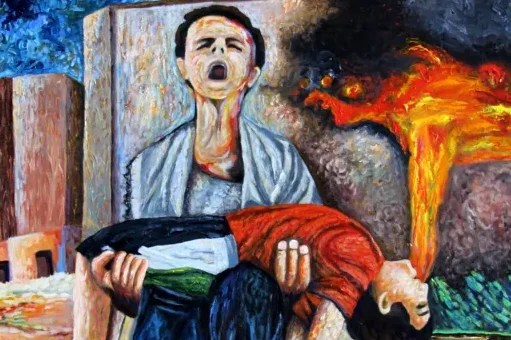

Meanwhile, right now, in Jesus’ own homeland, millions suffer starvation and terror, displacement and death under Western-funded Israeli colonialism and continued military assault. Israel blocks food from reaching them, leaving Palestinians in fear that any “supper” they can scrounge up might be their last.

After their meal, Jesus led his friends into the Garden of Gethsemane, where he prayed in anguish, fearing all he was about to endure: criminalization, torture, and a painful public death.

Jesus begs his friends to “stay awake” as he wrestles — just to be present, to make him feel a little less alone. How do we respond to Jesus’ plea by “staying awake” to Palestine’s current agony?

That question also leads me to ponder another: how does God join Palestinians in their agony? Where is God in their suffering?

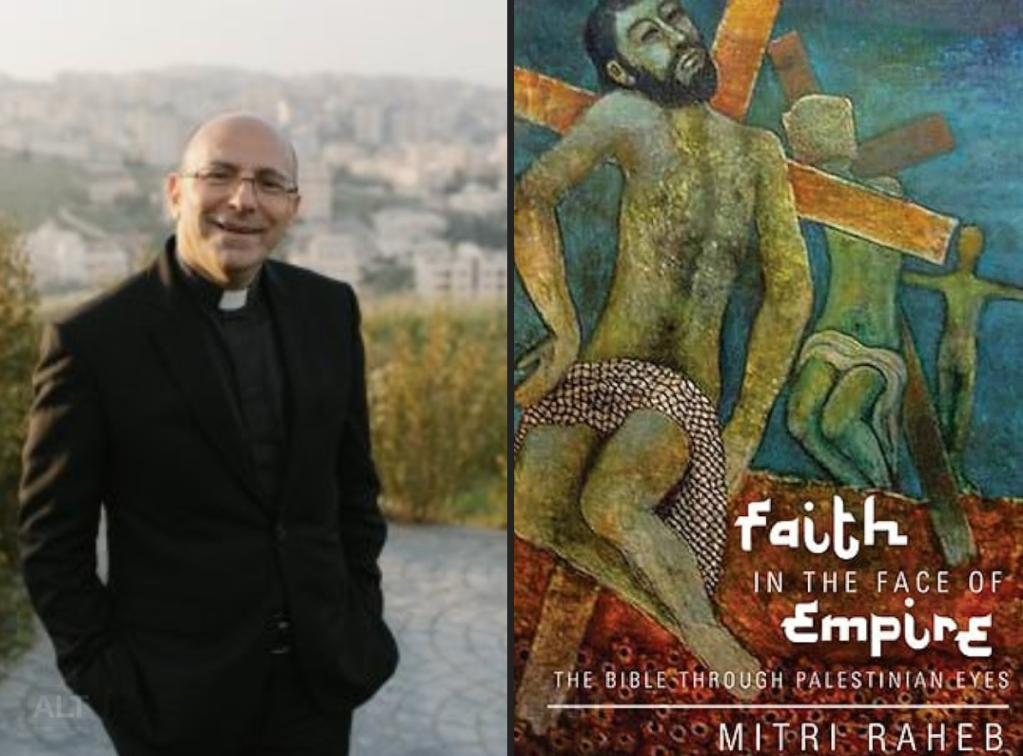

Palestinian Christian Mitri Raheb seeks to answer this question of where God is in his 2015 book Faith in the Face of Empire.

Raheb looks at the history of the Palestinian region, from ancient times to today, as a long chain of different empires — from the Assyrians to the Romans, Ottomans to Western-funded modern Israel.

He says that this long history of occupation is what gave Palestinians the ability to notice God where those in power do not: among the powerless. It is this revelation, Raheb declares, that has empowered Palestinians — Jewish, Christian, and Muslim — to survive and resist Empire again and again.

Raheb writes about how in ancient times, the divine was made

“…visible and omnipresent in the empire with shrines and temples that represented not only his glory but also that of the empire. God’s omnipotence and that of the empire were almost interchangeable. He was a victorious God, a fitting deity for a victorious empire.

At the other end of the spectrum there was the God of the people of Palestine, whose tiny territory resembled a corridor in Middle Eastern geography. …This God was a loser. He lost almost all wars, and his people were forced to pay the price of those defeats. In short, this God did not appear to be up to the challenge of the various empires. His people in Palestine were forced to hear the mocking voices of their neighbors who taunted them, ‘Where is your God?’ (Ps 42: 3, 10).

The revelation the people of Palestine received was the ability to spot God where no one else was able to see him. When his people were driven as slaves into Babylon, they witnessed him accompanying them. When his capital, Jerusalem, was destroyed and his temple plundered, they saw him there. When his people were defeated, he was also present. The salient feature of this God was that he didn’t run away when his people faced their destiny but remained with them, showing solidarity and choosing to share their destiny.

Consequently and ultimately, Jesus revealed this God on the cross, in a situation of terrible agony and pain, when he was brutally crushed by the empire and hung like a rebellious freedom fighter. The people of Palestine could then say with great certainty [that their God] ‘in every respect has been tested as we are’ (Heb 4:15).

For the people of Palestine this meant that defeat in the face of the empire was not an ultimate defeat. It meant that after the country was devastated by the Babylonians, when everything seemed to be lost, a new beginning was possible. Even when the dwelling place of God was destroyed, God survived that destruction, developing in response a dwelling that was indestructible. And when Jesus cried on the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mk 15:34), that soul-rending plea was just the prelude to the resurrection…”

It is this revelation that God sides against empire, Raheb continues, that keeps the Palestinian spirit alive through horrible oppression. Though the world may call such faith foolish — how can you believe God is with you and that God will have the final say, when all evidence points to your abandonment and defeat? — it is wisdom to the oppressed. Raheb describes how this wisdom feeds Palestinian resistance, over and over across the millennia:

“The art of survival and starting anew is a highly developed form of expression in Palestine, and one I see daily. People’s lives, businesses, and education are interrupted by wars and the aftermath of wars over and over again, and yet I witness people refusing to give up, taking a deep breath, and beginning again. Logically, it is foolish, and yet there is deep wisdom in such a course of action.

I’m often asked by visitors how I can keep going. Everything seems to be lost, the land “settled” by Israel, the wall suffocating Palestinian land and spirit, the world silent, and hope almost gone.”

Raheb’s answer to them is that God’s presence in and among the suffering, and God’s promised resurrection, of renewal in the face of all terror and death, is what keeps him and his people going.

As we enter into these final days of Lent, I pray for hearts and minds opened to witnessing God’s solidarity with and resurrection for Palestinians suffering imperial brutality. I pray that the Palestinians will survive as they always have — “afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed” (2 Cor 4:8–9).